Since the beginning of summer, discussions on post-war electoral legislation have intensified in the Ukrainian political establishment. In late June, Chairman of the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine Ruslan Stefanchuk noted that the parliament is developing a bill on organizing elections after the end of the war. Almost simultaneously, in late June and early July, two draft laws amending the Electoral Code were registered in parliament: No. 13419 of June 25, 2025, and No. 13464 of July 10, 2025. The first draft law proposes introducing a plurality electoral system for local elections in communities with up to 50,000 voters, while the second aims to introduce significant changes to the electoral system for parliamentary and local elections, which, conversely, would strengthen party influence.

Despite the existence of expert documents (the White book on the preparation and organization of post-war elections or OPORA’s Roadmap for ensuring the organization of post-war elections), Members of Parliament did not begin with urgent security issues or the realization of electoral rights for voter groups vulnerable due to the war (including military personnel and internally displaced persons). Instead, politicians primarily focused on the electoral system.

It is essential to emphasize that these are not temporary measures to mitigate the consequences of the war, but rather permanent changes. If adopted, they will have a fundamental and long-term impact on the political system. The development of such a significant initiative occurred without proper communication and explanations to the public. However, socially important decisions should be developed openly, jointly with civil society, and with adherence to the principle of inclusivity at all stages, from identifying key problems to finding optimal solutions.

Civil Network OPORA analyzed these draft laws. None of them offers a comprehensive approach to addressing key challenges caused by Russia’s full-scale aggression against Ukraine, such as multi-million internal and external migration, the destruction of electoral infrastructure, security risks, expected Russian Federation interference in the electoral process due to unregulated campaigning, disinformation in social networks, etc. Instead, the draft laws only propose to modify the systems for parliamentary and local elections.

OPORA has repeatedly emphasized the need to transfer substantive and professional work on electoral reform to the parliament, both in the context of Ukraine’s European integration commitments and for a comprehensive solution to the problems of organizing the first post-war elections. The recently registered legislative initiatives can catalyze these processes, even if, due to Russian aggression, parliament does not consider them at this stage. At the same time, the start of preparations for post-war elections does not mean the start of a political race, but rather demonstrates a strategic vision for the country’s future development.

To ensure that the discussion on future electoral rules, including electoral systems, is not superficial, we will examine these draft laws in detail, including their main advantages and disadvantages, potential risks, and opportunities. Understanding that determining the electoral system is a political issue that falls within the exclusive competence of parliament, any final decision to change it must be duly justified, based on specific calculations and modeling, and take into account Ukrainian realities and international experience. This approach will help avoid political motives and create a stable, transparent, and fair electoral system that fits post-war realities and helps strengthen democracy.

Disclaimer. Before proceeding to evaluate the aforementioned bills, it is important to note some established positions in international and national practices regarding electoral systems:

This draft law proposes significant changes to the systems of parliamentary and local elections.

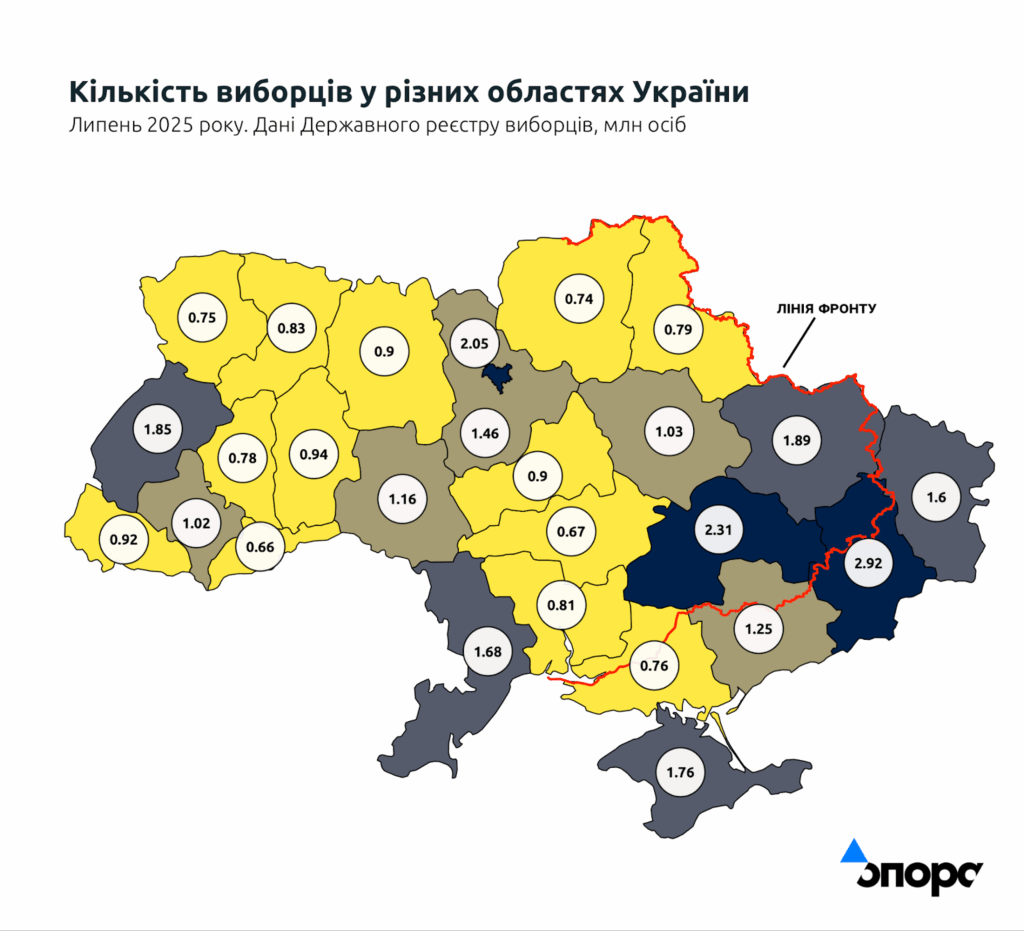

Forming of Regional Lists:

The proposed innovation — establishing a different fixed number of candidates for elections to the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine depending on the electoral region — is not based on relevant data. This is likely because it uses current State Voter Register (SVR) figures, according to which, as of July 2025, Ukraine had 32.4 million voters with an electoral address (the largest numbers being in Donetsk Oblast — 2.9 million, Dnipropetrovsk Oblast — 2.3 million, and the city of Kyiv — 2 million; the smallest in Chernivtsi Oblast — 664 thousand, and Sevastopol — 264 thousand). However, given the large-scale migration processes and temporary occupation, these data do not reflect the actual state of affairs.

For example, when calculating the number of candidates in the Southern Electoral District (№16), voters from temporarily occupied territories — Sevastopol, Nova Kakhovka, Henichesk, etc. — are taken into account. Similarly, the Donetsk electoral region (№5) includes voters from Bakhmut, Avdiivka, Vuhledar, and other occupied cities. This distorts the real electoral picture and calls into question the validity of such an approach.

According to OPORA’s calculations, excluding Crimea and Sevastopol, the territory of 157 communities in Ukraine is either fully or more than two-thirds occupied. This amounts to approximately 4,200 polling stations, encompassing 5 million voters. In the territory of Crimea and the city of Sevastopol, there are an additional 1,430 polling stations (1.7 million voters) under occupation. The territories of 19 communities (200,000 voters) are partially occupied.

Accounting for the number of voters in a particular region could align with best practices if the number of mandates distributed in the regions depended on the number of registered voters. This would ensure stable proportional representation of all regions in parliament, regardless of fluctuating turnout figures. Due to security threats, especially in the territories that have suffered significant destruction and/or are located near the demarcation line, turnout could be very low.

However, it should be considered that a fixed number of mandates in the regions can also lead to negative consequences, such as inter-regional polarization, where representatives of more populated regions will be dissatisfied that less populated regions receive disproportionately high representation in parliament. This would also necessitate a transition to a regional electoral quota, which, given significant differences in the “number of votes required to obtain one mandate,” would only intensify accusations of violating the principle of equal elections.

In the event of a transition to a fixed number of candidates and mandates in electoral regions, it is important for legislation to include a formula for calculating the number of mandates that would account for the consequences of migration processes. Such a formula should be based on up-to-date data regarding the number of voters in the region at least one month before the start of the electoral process.

At the same time, it is first and foremost important to adapt the parliamentary electoral system to account for the expansion of occupied territories.

Another significant drawback of the draft law No. 13464 is the abolition of the requirement for a minimum number of candidates on a regional list. This creates the risk that parties will manipulate the lower and upper limits when nominating candidates in electoral regions, in order to increase the share of “residual” votes, which would then be directed towards the distribution of mandates via the closed nationwide list. This approach undermines the idea of open lists and strengthens the parties’ monopoly on political representation.

Given the alphabetical placement of candidates in a regional list, the transition to a percentage-based gender quota is quite logical. However, its implementation in absolute figures (30%) will have worse prospects than the current model, which allows for gender representation at around 40%, as clearly illustrated in the 2020 local elections.

Despite the modification of the approach to the gender quota in the regional list, the draft law does not propose any changes aimed at counteracting the non-fulfillment of the gender quota, particularly in cases where a person, after being elected, fails to submit documents for their registration as a Member of Parliament or when replacing Members of Parliament whose powers have been prematurely terminated. This creates a risk of formal adherence to the quota during list submission and an actual circumvention of the principle of gender-balanced representation.

The proposed ballot paper option is better than the current one due to the placement of the field for writing down the candidate’s number next to the field for marking the party. Placing such a field at the bottom of the ballot does not promote personalized voting for specific candidates. An inconvenient location for the specific candidate’s number field can lead to voters only casting a vote for the party and overlooking or avoiding supporting its representative.

During OPORA’s study, “How voters perceive different types of ballot papers to improve the election process” (2021), not all focus group respondents noticed the field for voting for a separate candidate at the very end of the ballot paper. Overall, respondents rated this method of entering a candidate’s number as the least convenient way to arrange the layout elements. The study also recommended avoiding postal code-like markings for entering the numbers of candidates from political parties, as most respondents do not remember the correct way to write numbers using the coding accepted in postal services. Even if such writing is not mandatory, it creates unnecessary doubts for respondents. In cases where abandoning such writing is impossible, it would be advisable to at least print the list of candidates with exactly those numbers so that voters can simply copy the desired one. On the other hand, digital markings in the filling area improve the understanding that a number should be entered into that specific field, but such markings should still follow some generally accepted style.

While envisioning changes in the ballot paper form—specifically, placing two squares to the right of each party’s full name (an empty one for expressing a vote for the party, and one with a stencil for expressing a vote for a candidate from the party’s corresponding regional list)—the bill does not amend the provisions that define the conditions for invalidating a ballot. This creates a risk of ambiguous interpretation of the election results. According to the current version of the Electoral Code, a ballot is considered invalid if no mark is placed next to the full name of a political party. In this regard, the question arises: will a ballot be considered valid if the voter indicated a candidate’s number but did not mark the party?

Despite the criticism of the so-called “guaranteed mandates,” which was one of the reasons for the President to veto the Electoral Code in 2019, the number of such mandates will increase even further under the proposed model. In addition to the 9 candidates on the nationwide list, the first candidate in each regional list will also have a privileged right to a mandate—regardless of voter support. This approach significantly weakens the idea of open lists, as voters will effectively have no influence on the distribution of at least 34 mandates, shifting the emphasis towards the “closedness” of the system. Furthermore, it creates conditions for the leadership-type regional lists, where the main emphasis will be placed on the first candidate.

The abolition of the 25% threshold of the electoral quota for advancement in regional lists, on the one hand, corresponds to the political agreements reached during the IX Jean Monnet Dialogue on November 10-12, 2023 (p. 5), and appears to ensure the competitiveness of candidates within a single party list. On the other hand, coupled with other proposed innovations, such a decision can lead to negative consequences. Ukraine has one of the strictest models for advancement on lists among European countries. In many states, achieving 5% of votes or a higher result compared to other candidates on the list is often sufficient. At the same time, the latter approach can provoke excessive intra-party competition, which harms the campaign. Therefore, establishing such a “legitimacy barrier” is considered more justified, especially in conditions of low political culture, party weakness, and high risks of dishonest competition.

Granting the central governing body of a party the ability to determine the electoral list by which a candidate, who is entitled to a guaranteed mandate in the nationwide constituency (a candidate from the top nine) and at the same time received a mandate from a regional list, will be declared elected, creates a risk of manipulating voter expectations. In its Decision of the Grand Chamber of the Constitutional Court of Ukraine of December 21, 2017, №3-р/2017 (case on the exclusion of candidates from the electoral list), it was emphasized that the state has an obligation to ensure the free expression of citizens’ will and respect for its results through proper regulation of the electoral process, adherence to democratic procedures, and effective control that prevents abuse and manipulation (para. 3, sub-para. 2.4, point 2 of the reasoning part). Recently, in its decision of July 10, 2025, the ECHR in the case of Tomenko v. Ukraine, guided by the position of the Venice Commission and its previous practice (in particular, the Paunović and Milivojević case), emphasized that deputies hold a mandate from the people, not from their parties, which are merely institutional intermediaries, and it is not a party that controls the social contract between voters and parliament.

Therefore, the involvement of candidates with guaranteed mandates in regional campaigns lies in the realm of political calculations and is evidence of the formal openness of the electoral model, which in practice strives to retain the characteristics of a closed and controlled system.

Furthermore, the bill does not contain a mechanism for replacing a guaranteed mandate if the party decides that such a candidate receives a mandate from the regional list. Such regulation will incentivize parties to choose in favor of the nationwide list, and thus, “close” the list.

Unified Electoral System for All Councils:

The proposed mechanism will not comply with international obligations, particularly paragraph 7.5 of the OSCE Copenhagen Document of 1990. According to this document, OSCE participating states undertook to “respect the right of citizens to seek political or public office, individually or as representatives of political parties or organizations, without discrimination.” This was noted by ODIHR mission representatives in their final report on the observation of the local elections on October 25, 2020 (p. 10). This will also contradict the requirements of the Functioning of Democratic Institutions Roadmap, the implementation of which should facilitate Ukraine’s accession to the EU.

In our country, the practice of self-nomination in local elections is widespread. In 2020, in communities with up to 10,000 voters, 32% of all candidates for local councils ran as self-nominated candidates. Among all elected city, settlement, and village heads, almost 47% of the winners were self-nominated, and among deputies of territorial communities with up to 10,000 voters, 39.2% of self-nominated candidates won mandates. This indicates that in Ukraine, the practice of voting for independent candidates remains the most popular within the framework of electoral systems that provide such an opportunity.

Furthermore, the possibility of self-nomination of candidates (in one form or another) in local elections is provided for in most European countries within proportional systems. This possibility is realized through lists of independent candidates. The introduction of such a model in Ukraine would allow for the filling of vacant deputy mandates without by-elections, which is especially important in wartime conditions. This would help preserve the functionality of local self-government bodies and prevent excessive centralization of power through military administrations in case it is impossible to hold interim elections.

Additionally, in the White Book on the Preparation and Organization of Post-War Elections (prepared by experts from OPORA, Centre for Policy and Lawl Reform, and IFES), the authors draw attention to the following negative aspects (pp. 38-39):

The alphabetical placement of candidates in the territorial list is a consequence of abolishing the 25% threshold of the electoral quota for advancement on the list. With such a threshold, parties had a reason to arrange candidates by order, as it was more difficult for voters to change the order of mandate acquisition. Now, a candidate only needs a minimal number of votes to move up the list, which negates the importance of the first candidate, whose mandate is no longer guaranteed. At the same time, the possibility of registering a minimum number of candidates on the regional list will contribute to the closed nature of the system, reduce competition, and increase the number of residual votes that will be reallocated to the single list.

The initiators of the draft law propose a transition to a “percentage-based” gender quota, analogous to what is suggested for parliamentary elections, which is entirely logical given the alphabetical placement of candidates in the regional list. However, as previously noted, introducing a gender requirement in absolute figures (30%) will have worse prospects than the current model, which allows for gender representation at around 40%. This was vividly illustrated by the 2020 local elections—the effect of gender quota was impressive. Among all candidates, 44.7% were women, and about 37% of women were elected to various levels of councils in Ukraine.

As with parliamentary elections, despite the modification of the approach to the gender quota in the territorial lists, the draft law in no way proposes a solution to the problems observed with adherence to the gender quota in the 2020 local elections. For instance, despite the legally established obligation to comply with the gender quota, some electoral process actors tried to ignore it during the nomination and registration of candidates or circumvent it by encouraging women to withdraw their candidacy after the electoral list was registered by the respective election commission, or to give up their representative mandate, which ultimately contributed to the election of more men. Furthermore, there was widespread judicial practice where non-compliance with the gender quota was interpreted as a technical error and allowed to be corrected.

In this regard, OPORA, in its Final Report on the results of observation of the 2020 local elections, emphasized that the next stage of electoral reform should include the improvement of procedures for ensuring the gender quota in the electoral lists of local political party organizations at the stage of their registration, the cancellation of registration of individual candidates from such lists, and the preservation of gender balance in elected bodies of power during the distribution of mandates. This problem was also highlighted by the OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) in its monitoring mission report on the observation of the 2020 local elections. It recommended that Ukraine consider compliance with the gender quota for candidate lists at all stages of the electoral process, especially during nomination and registration.

As with parliamentary elections, the abolition of the 25% threshold of the electoral quota for advancement in territorial lists can lead to excessive intra-party competition and create additional incentives for voter bribery. Therefore, OPORA consistently supports the idea of lowering the electoral quota to 5%, rather than abolishing it entirely.

A positive step is the abandonment of automatically granting a mandate to the first candidate on the single party list. This eliminates a widespread practice where well-known individuals (MPs, top officials) are nominated as first numbers solely to boost party ratings, without a genuine intention to participate in the work of local councils. This enhances voter influence on mandate distribution and reduces the formality of leadership positions in party lists.

The draft law envisages raising the threshold for applying the majoritarian system.

In 2020, Civil Network OPORA already criticized the excessively low threshold for applying the proportional electoral system in communities with 10,000 or more voters. We emphasized the significant risks of such “partification,” which substantially limits citizens’ ability to self-nominate in local elections, could lead to undesirable polarization of Ukrainian regions based on election results, and also intensifies the politicization of local self-government bodies through party control over their nominees via recalling local council deputies. However, it is worth noting that after the introduction of martial law due to the full-scale Russian invasion, such “partification” contributes to ensuring the functionality of many local councils by replacing their deputies from the electoral list.

At the same time, raising the threshold for applying the majority system, although it has a number of significant advantages, such as strengthening ties with voters, must be based on specific calculations and modeling of its impact on a significant portion of communities and, as a result, on the development of municipal democracy.

So, as of July 2025, 1470 communities have been formed in Ukraine (excluding Crimea and the city of Sevastopol). According to the State Voter Register portal, information on 1773 communities can be obtained. However, 302 of them are located in Crimea, and one more is the city of Sevastopol. Also, according to OPORA’s calculations, the territory of 157 communities is either fully or more than two-thirds occupied. The territory of another 19 communities is partially occupied.

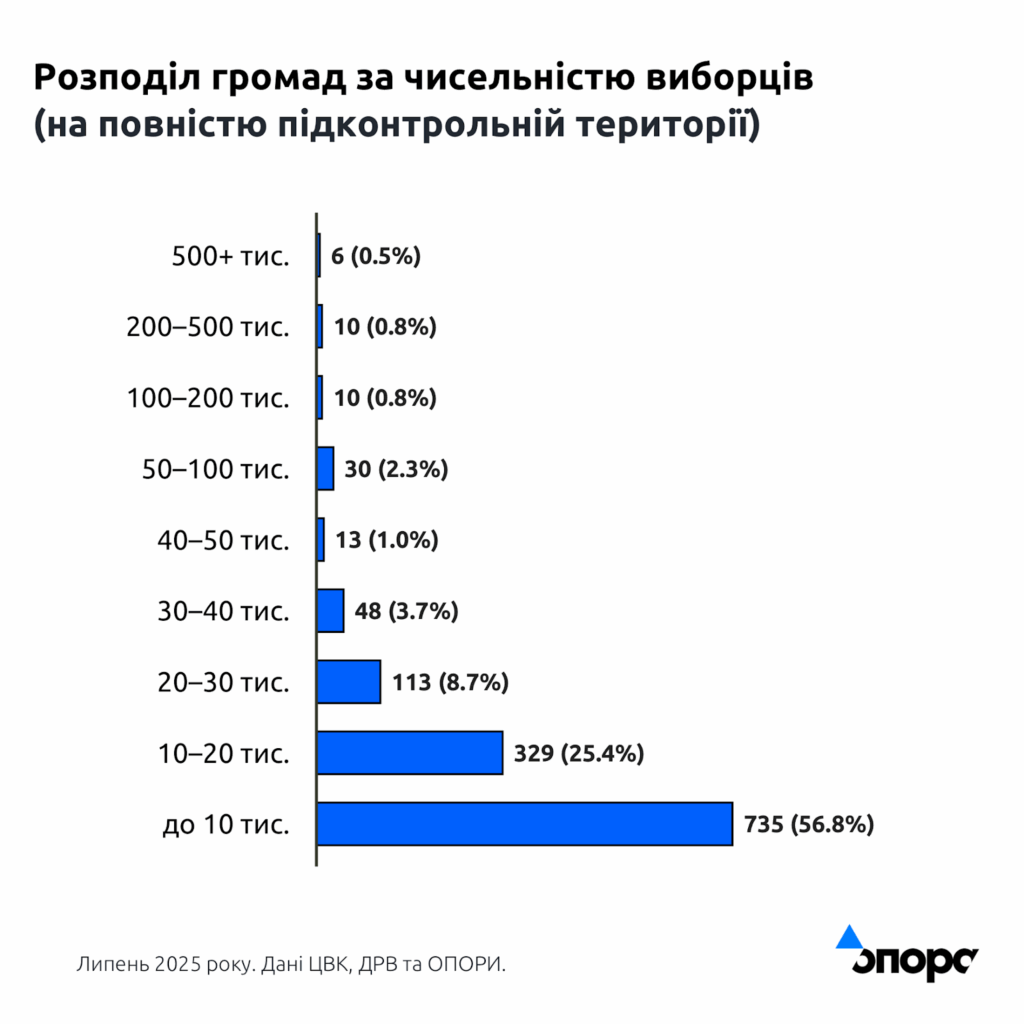

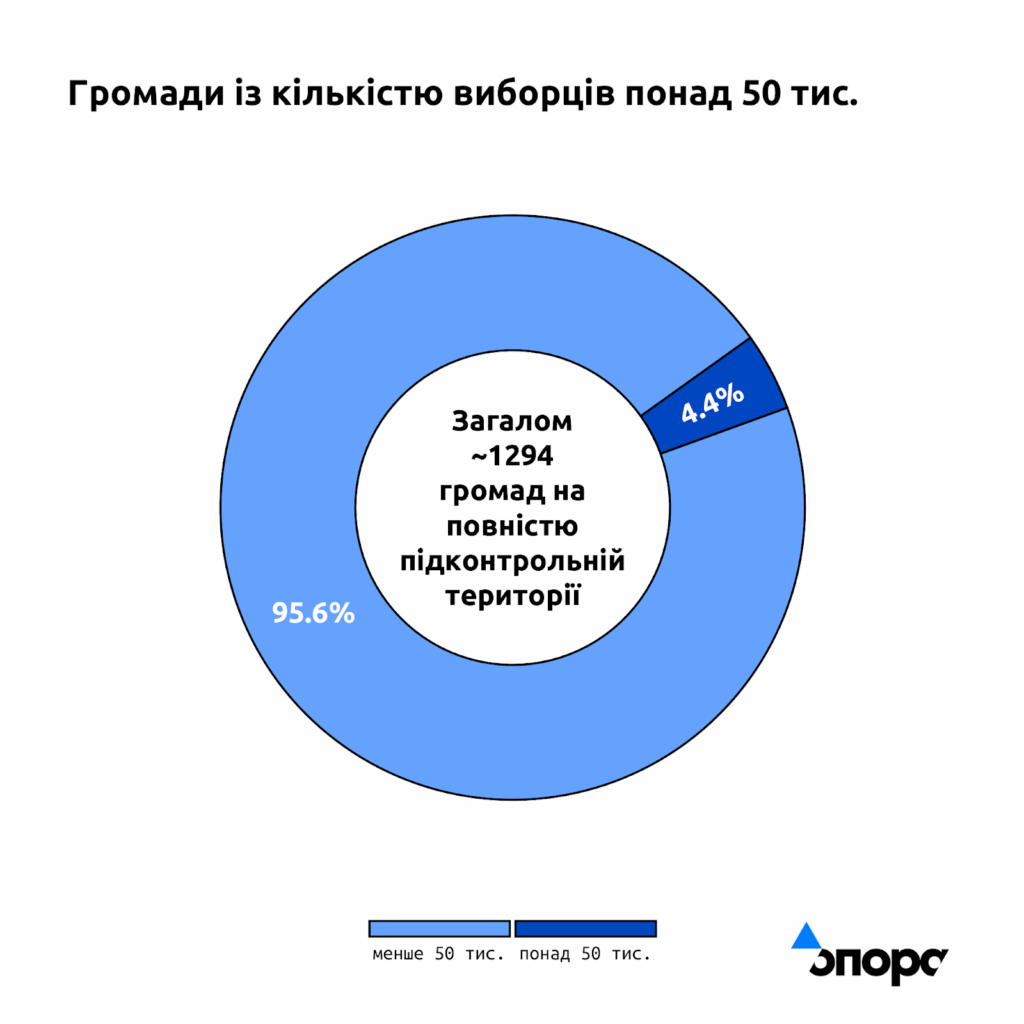

Among the communities fully under Ukraine’s control, the largest category is those with up to 10,000 voters. There are 735 such communities (56.8%). There are 329 (25.4%) communities with 10-20 thousand voters, 20-30 thousand — 113 (8.7%), 30-40 thousand — 48 (3.7%), 40-50 thousand — 13 (1%), 50-100 thousand — 30 (2.3%), 100-200 thousand — 10 (0.8%), 200-500 thousand — 10 (0.8%), and over 500 thousand — 6 (0.5%).

Currently, the share of communities with fewer than 50,000 voters is 95.6%. This accounts for 1238 communities where 13.8 million voters (54%) have registered electoral addresses. In communities with over 50,000 voters, 11.75 million voters (46%) are registered. Given this, the widespread application of the majoritarian electoral system will effectively cover almost all communities in the country and will inevitably be accompanied by its classic disadvantages—vulnerability to bribery; weak party competition; and the risk of mandates remaining vacant for prolonged periods in cases of early termination of deputies’ powers when by-elections are impossible. Such an approach could significantly affect the functionality of local councils and weaken the development of the party system at the local level—if not halt it entirely. At the same time, the majoritarian system remains clear to voters, contributes to strengthening the connection between citizens and deputies, and increases the accountability of elected representatives.

Ultimately, OPORA’s main concern is that the authors of the bill do not justify the choice of community size and do not consider the long-term effects of the proposed changes. Any innovations must be based on current data, provide for an assessment of consequences, and correspond to a legitimate goal and public interest. If different electoral systems are applied for each local election, the effect of their application will be primarily technical and, likely, negative.

Beginning work on legislation for post-war elections is an important and necessary step. For this work to be successful, it is crucial to immediately define clear priorities, which undoubtedly include guaranteeing the rights of all voters and the security of the electoral process. Instead, the registered draft laws primarily shift focus to the mechanics of electoral systems, leaving aside comprehensive solutions for millions of military personnel and displaced persons, as well as security issues at polling stations.

A discussion about the optimal electoral model is, of course, necessary, but it must be derived from the main goal, which is the protection of citizens’ electoral rights. It is important to ensure that any changes do not create unintended risks, such as an imbalance of representation or increased party control as opposed to the will of citizens. Creating effective and sustainable legislation is possible only through an inclusive dialogue that involves open cooperation in parliament with the participation of civil society, experts, and representatives of groups whose rights are most vulnerable. Such an approach, based on data and trust, will allow for the development of a system that truly strengthens Ukrainian democracy.

Subscribe to our

newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter

and receive the latest EPDE news

Subscribe to our

newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter and receive the latest EPDE news