Observation of the presidential election is carried out by the Belarusian Helsinki Committee and the Human Rights Center “Viasna” in the framework of the campaign “Human Rights Defenders for Free Elections”.

CONCLUSIONS

The pre-election period was characterized by an economic decline against the background of contradictions in Belarusian-Russian relations and a considerable budget shortfall caused by a fossil fuels trade crisis. The situation was aggravated by the growing demands from the Russian side on the political agenda of bilateral relations and the linking of economic issues with “advanced integration” within the framework of the creation of the Union State of Russia and Belarus.

Foreign policy relations between Belarus and the EU countries and the United States, in turn, tended to progressively improve, taking into account, among other things, certain processes towards a dialogue on human rights, both domestically and on international platforms.

The Belarusian authorities have not implemented a single recommendation by the OSCE and national observers made following the previous elections.

The presidential election was held against the backdrop of the coronavirus pandemic, which obviously influenced the electoral preferences of voters. Despite the fact that, in general, the country applied a mild anti-epidemiological policy, including the government’s refusal to introduce serious quarantine measures, the CEC introduced special procedures that significantly reduced the level of transparency of electoral procedures, especially at the stage of voting and counting of votes.

The 2020 presidential election was held in an unprecedented atmosphere of fear and intimidation of society, against the backdrop of repression, which began almost immediately after the announcement of the election and marred every electoral phase. As a result of this repression, more than a thousand citizens were subjected to arrests, while hundreds were sentenced to short terms in prison or fined. Criminal cases targeted 23 people, including direct participants in the election: members of nomination groups and presidential nominees, as well as bloggers and participants in peaceful protests and pickets held to collect support signatures. All of them were called political prisoners by the Belarusian human rights community.

One of the most popular potential candidates, Viktar Babaryka, was arrested and taken into custody at the stage of collecting signatures. Several members of his nomination group were arrested, too, including the nominee’s campaign manager Eduard Babaryka. Popular blogger Siarhei Tsikhanouski, who also announced his decision to run for president, was arrested to serve an earlier sentence of administrative detention and was unable to personally submit documents for registration of his nomination group. As a result, his wife Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya decided to stand in the election. After his release and active participation in the election campaign of Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya as the head of her nomination group, Tsikhanouski was again arrested as a result of a provocation. He was soon charged with organizing group actions that grossly violated public order, and at the end of the election campaign — with preparing for and organizing riots. In addition, Tsikhanouski faced a charge under Art. 191 of the Criminal Code after a personal complaint by the CEC Chairperson Lidziya Yarmoshina.

The electoral process at all of its stages did not comply with a number of basic international standards for democratic and fair elections and was accompanied by numerous violations of these principles and requirements of national legislation. This was due to the active use of administrative resources in favor of the incumbent, the absence of impartial election commissions, unequal access to the media, numerous facts of coercion of voters to participate in early voting, and the closed nature of a number of electoral procedures for observers.

The CEC’s imposition of restrictions on the number of observers at polling stations led to the disruption of observation of all types of voting (early voting, voting on Election Day, and home voting), as well as the counting of votes. These important stages of the election were completely opaque.

Significant violations of national legislation and the fundamental principles of fair and democratic elections, including the deprivation of observers’ right to monitor the counting of ballots, do not give grounds to trust the election results announced by the CEC or consider them as a reflection of the actual will of the citizens of Belarus.

Election commissions

When forming the election commissions, executive committees applied a discriminatory approach to representatives of opposition parties: out of 25 candidates from opposition parties, only two were included in the TECs, and out of 545 candidates nominated by opposition parties, only 6 people were included in the PECs (1.1%). Representatives of opposition parties in the TECs accounted for 0.1% of their members, and in the PECs — 0.009%, which is five times less than in the 2015 presidential election.

Most members of election commissions traditionally represented the five largest pro-government public associations: the Belarusian Republican Youth Union (BRSM), Belaya Rus, the Women’s Union, the Union of Veterans, and trade unions of the Federation of Trade Unions of Belarus (FPB).

The absence in the electoral legislation of guarantees for the representation in election commissions of representatives nominated by all political actors taking part in the elections, as before, resulted in an arbitrary and discriminatory approach towards opposition parties and movements.

Nomination and registration of candidates

55 people submitted documents for the registration of their nomination groups, which is an all-time record in the entire history of presidential elections in Belarus. The CEC registered 15 of them, which accounted for 27% of the total number of considered applications.

Refusals to register some nomination groups alleging violations of voluntary participation in elections testify to manipulations by the CEC with the provisions of the Electoral Code and violate the principle of equality of candidates. The results of consideration of appeals against refusals to register nomination groups by the Supreme Court demonstrated the ineffectiveness of this remedy for electoral campaign participants.

The collection of signatures was marred by serious violations of the standards of free and democratic elections. The nomination groups of some contenders were under significant pressure from law enforcement agencies. Some of the members of the nomination groups of Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya and Viktar Babaryka were arrested and taken into custody within the framework of a series of criminal cases, including presidential nominee Viktar Babaryka himself. Their persecution was condemned as politically motivated by the Belarusian and international community, and the detainees were called political prisoners.

The election commissions confirmed the collection of the required 100,000 support signatures by six potential candidates. The verification of signatures, as before, was not transparent. An additional reason for mistrust in its results and a subject of a wide public debate was the fact that the CEC validated thousands of signatures which were not reported by two potential candidates.

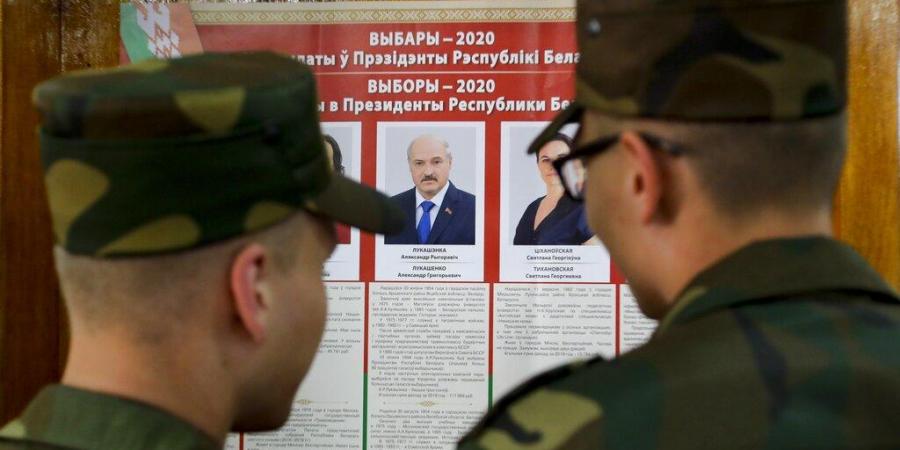

Of the seven persons who were nominated for the presidency and submitted the signatures collected for their nomination, five were registered as candidates: Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya. Andrei Dzmitryeu, Hanna Kanapatskaya, Siarhei Cherachen, and Aliaksandr Lukashenka.

Candidate registration was marked by violations of the standards of fair elections. Viktar Babaryka was denied registration based on confidential information provided by the State Control Committee, an authority investigating the nominee’s criminal case, which contradicts the principle of the presumption of innocence. The CEC’s decision to disqualify Viktar Babaryka violated his right to be elected.

The selection of illegal picketing places for collecting signatures did not create serious obstacles to the collection of signatures by the nomination groups. The absence of a unified approach of local authorities to the definition of such places was noted, however.

The permission to collect signatures on the territories of enterprises and institutions created additional conditions for the illegal use of administrative resources in support of the current head of state, as the collection of signatures for the nomination of Aliaksandr Lukashenka was often carried out during working hours, on the territory of enterprises and institutions, with the direct participation of their administrations.

Election campaigning

The election campaign significantly differed from the previous elections by the wide public activity of the protest electorate, both in Minsk and smaller Belarusian cities. The campaign of Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, supported by representatives of the joint headquarters, became the most active and noticeable in society. Rallies in her support were attended by tens of thousands of people in different cities of the country.

Opportunities to receive information about presidential candidates were severely limited by local executive committees, which sharply reduced the number of locations for election campaigning, as compared to the 2015 presidential election. In many cases, these places were unsuitable for campaign purposes (remote, with poor transport accessibility, etc.).

The phase of election campaigning took place in unequal conditions: having abandoned official campaigning, the current President made the most of the administrative and propaganda resources of the vertical of power, pro-government public organizations and the media. The President’s annual address to the Belarusian people and the National Assembly, postponed from April to August 4, was widely circulated in the media, which constituted illegal campaigning for the head of state as one of the candidates. In the regions, meetings of the incumbent’s proxies and representatives of the authorities of different levels with labor collectives were intensively organized. They were held during working hours, at workplaces and were not always announced; journalists were not allowed to attend some of these meetings or were forbidden to take photos.

Campaigning for the incumbent was accompanied by a wide campaign of discrediting the most active presidential candidates. The government-owned television channels used facts of criminal prosecution of election campaign participants and criminal case files, which violated the presumption of innocence. For the first time ever, Telegram channels were actively used to promote the negative image of alternative candidates and their programs, as well as to discredit them.

Several incentive measures taken at the initiative of the incumbent, including increasing retirement pension rates and re-scheduling their payment to an earlier date, were actually bribery of voters and the use of administrative resources.

The headquarters of alternative presidential candidates actively used the Internet and social media to campaign in favor of their candidates, as well as the YouTube video service.

Early voting

41.7% of voters took part in early voting, which is an all-time record for the presidential elections in Belarus. In fact, early voting has become the norm, which does not meet the requirements of the Electoral Code.

The restrictions imposed by the CEC on the number of observers at polling stations during early voting made this electoral phase completely opaque for independent public observation.

Of the 798 observers of the observation campaign “Human Rights Defenders for Free Elections” accredited at polling stations during the early voting period, only 93 (11.6%) had the opportunity to observe part time at polling stations, which did not cover the entire voting period. Only one campaign representative had the opportunity to observe during all five days of early voting.

During early voting, observers of “Human Rights Defenders for Free Elections” documented numerous facts of organized and forced voting of certain categories of voters (military personnel, employees of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, Ministry of Emergency Situations, employees of government-owned enterprises, citizens living in dormitories), as well as facts of inflating the voter turnout.

The practice of early voting remains one of the systemic problems of the electoral process, creating ample opportunities for the use of administrative resources and other manipulations.

Voting at polling stations and counting of votes

Voter lists at polling stations remain closed to observers. A unified voter register has not been created. This creates conditions for turnout manipulation.

Observers of “Human Rights Defenders for Free Elections” were deprived of the opportunity to directly observe voting at polling stations, as well as home voting.

Where observers were allowed to monitor outside polling stations, e.g. in many polling stations in Minsk and Brest, large queues of voters were observed, and in some cases, the total turnout exceeded 100%. In many cases, voters did not manage to vote before the polling stations were closed. These facts once again confirm the clear overstatement of the early voting turnout.

The legislation does not provide for the method of counting ballots by precinct election commissions. There is no clear-cut procedure for counting votes, whereby the mark on each ballot is announced aloud and the ballot is displayed to all PEC members and observers present.

Due to the fact that observers of “Human Rights Defenders for Free Elections”, as well as observers of other civil initiatives, were not allowed to observe the counting of votes, there is every reason to assert that the establishment of the voting results was completely opaque. This is a violation of one of the fundamental principles of elections — the transparency of their conduct.

Electoral complaints

Petitions and complaints about violations of the Electoral Code during various stages of the election did not have a noticeable impact on election procedures. All appeals filed with the courts regarding decisions on the formation of election commissions (484) were either not granted (415) or left without consideration (69).

The consideration by the Supreme Court of appeals against the CEC’s decisions to deny registration to presidential candidates Viktar Babaryka and Valery Tsapkala also demonstrated formal approaches of the courts.

The filing of complaints and petitions remains an ineffective means of protecting the violated electoral rights of persons running for presidency, other electoral participants and observers.

The Electoral Code, as before, contains a limited list of cases subject to judicial appeal. The decision of the CEC on the establishment of the election results, as well as the corresponding decisions of the TECs, are not subject to judicial appeal.

In addition, the Electoral Code does not contain norms regulating the duration of procedural periods and conditions for their restoration. At the same time, the courts in their practice are guided exclusively by the norms of the Electoral Code, rather than the general norms of the Code of Civil Procedure. This legal uncertainty creates obstacles in exercising the possibility of appealing against violations of electoral rights by the subjects of the electoral process.

Observers of “Human Rights Defenders for Free Elections” submitted about three thousand complaints to various state bodies and higher election commissions during the entire period of the election. However, observers are not aware of a single case when complaints of gross violations at the stage of voting and counting of votes were granted.

Full report available below

Subscribe to our

newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter

and receive the latest EPDE news

Subscribe to our

newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter and receive the latest EPDE news